“A friend may be waiting behind a stranger’s face.”

Maya Angelou

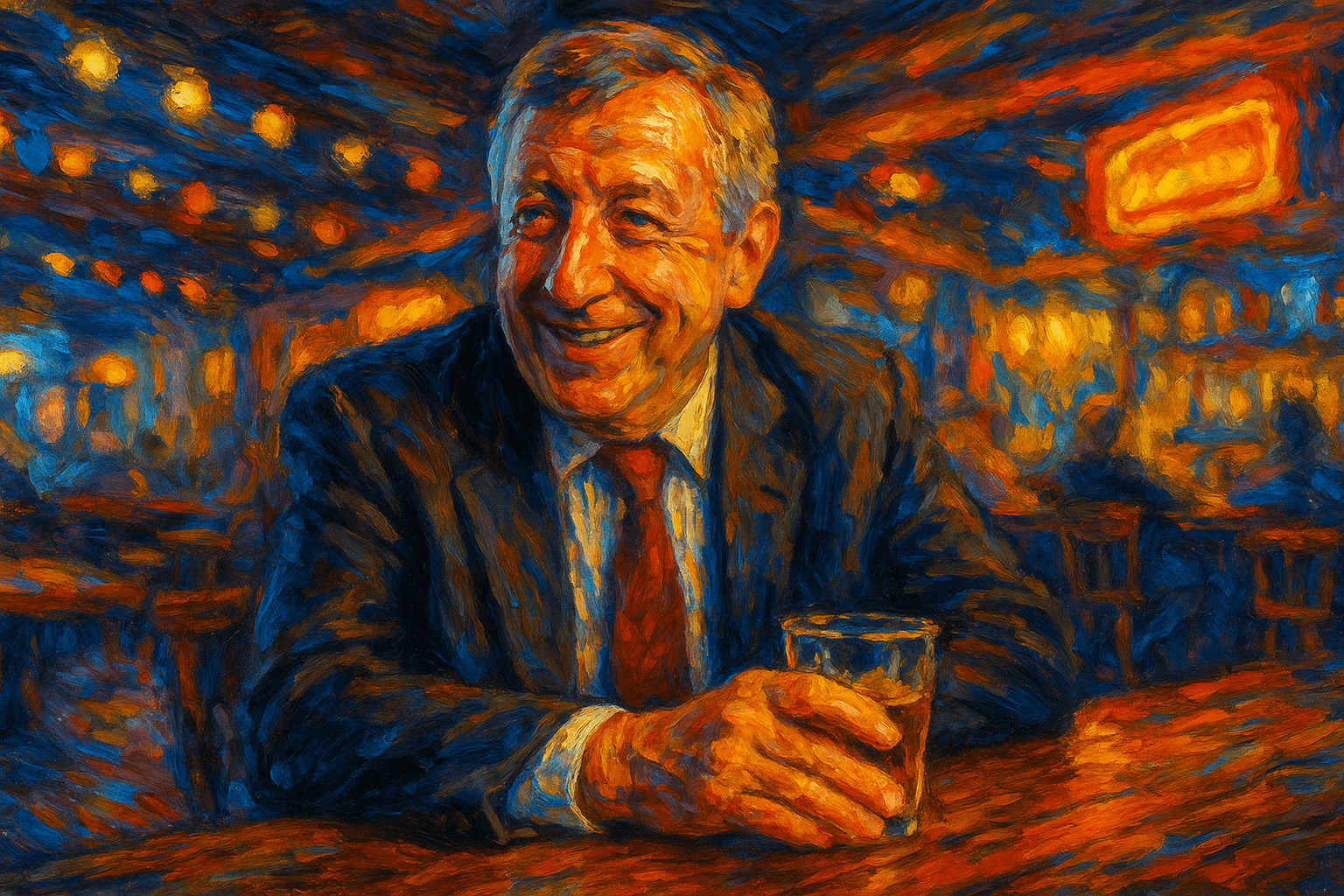

It was past midnight at a honky tonk in Nashville—the kind of place where the floor sticks a little, the band’s too loud, and somehow it’s exactly right.

I was there after a long conference day, brain fried, badge still around my neck, nursing the kind of bourbon that tastes like both a treat and a mistake.

Peter was there, too.

He was leaning against the bar, looking like the only man in the room who didn’t have somewhere else to be. Calm, measured, British—like he’d been shipped in to class up the joint.

We’d met earlier that day through a mutual acquaintance. Both of us were vendors—me running my scrappy little agency, him the CEO of a respected nonprofit that sounded important enough to have its own mission statement on a wall somewhere.

He had that kind of presence that made you sit up straighter, even in a room where people were line-dancing unironically.

He wasn’t there for the line dancing, of course. He was there to “observe the human condition,” which, at a Nashville honky tonk, is an ambitious choice.

Still, I joined him.

We started with polite small talk—the kind you have when you’re both pretending you won’t be friends—and then somehow wandered into the real stuff. Work. Family. Faith. The quiet panic that comes from wanting to do something meaningful without losing your mind in the process.

Maybe it was the bourbon, maybe it was Peter. But at some point, the whole night just blurred into this single, steady conversation—the kind that feels less like meeting someone new and more like remembering someone you’ve known for a long time.

I must’ve said something self-deprecating about being stretched too thin, about ambition and exhaustion and trying to keep all the plates spinning. Peter nodded, set down his glass, and said, very simply:

“You know, only three things really matter. Love your family. Love your friends. And do what’s in front of you.”

And then he took another sip, like he’d just said something about the weather.

At the time, I laughed. It sounded too simple.

But that’s the thing about Peter—he had a way of saying something that didn’t sound profound until it refused to leave your head.

Love your family.

Peter’s words weren’t advice. They were reminders.

Family’s always been my compass—Shelley, our two boys, the chaos and joy of it all. But I needed those words that night: love your family. Not in theory, not in sweeping declarations, but in the tiny, everyday ways that matter.

It’s not about grand gestures. It’s showing up for dinner, for the joke you’ve already heard, for the late-night conversation that starts as nothing and turns into something.

Peter gave me language for something I already believed: that love, at its best, isn’t loud—it’s consistent.

Love your friends.

Peter didn’t just say that, he lived it.

I didn’t know that night that it was the start of one of the most meaningful friendships of my life. But in hindsight, it was obvious.

He was curious, thoughtful, and so damn funny. Dry, British, quietly mischievous. The kind of guy who could make you laugh mid-sentence and then make you think about your entire life right after.

We had years of those conversations—over dinners, over drinks, over too many “quick chats” that lasted hours.

He was one of those rare people who made you feel seen, who never looked past you for someone more interesting. Love your friends wasn’t an idea to Peter—it was a practice.

Do what’s in front of you.

That one stuck the most.

Probably because it’s the hardest.

It sounds so simple: do what’s in front of you.

But it’s not simple. It’s everything.

It’s about presence—the kind that’s rare now.

It’s about actually seeing what’s right here instead of obsessing over what’s next.

Peter did that. Always.

He gave his full attention to whatever—or whoever—was in front of him.

And that’s what I think about most now, since he’s gone.

Peter passed away this year.

The world feels smaller without him, and quieter too. But his words—his way of being—are still here.

Love your family.

Love your friends.

Do what’s in front of you.

It’s not advice. It’s an orientation.

A way of moving through life that’s steady and good and full of grace.

I can still picture him that night—elbow on the bar, glass in hand, eyes full of kindness and something like mischief.

We laughed a lot that night. I’m glad that’s what I remember most.

And when I think of Peter now, I can almost hear him—calm, steady, maybe with a grin:

reminding me, in his quiet way,

to just do what’s in front of me.