“Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.”

Simone Weil

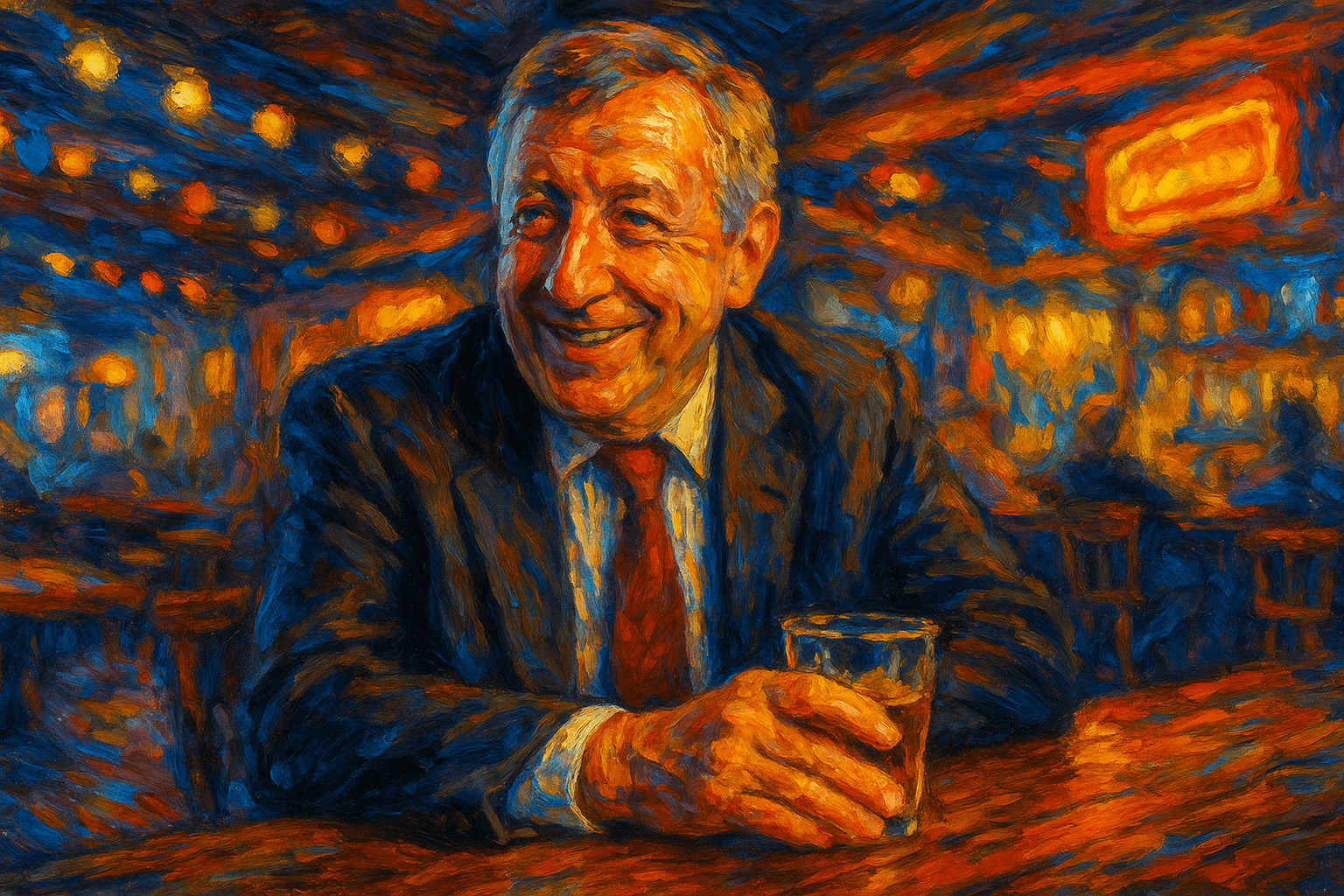

It was past midnight at a honky tonk in Nashville—the kind of place where the floor sticks to your shoes and nobody apologizes for it. The band was too loud, the lights were too bright, and every square inch of the place felt like it had been mopped with barbecue sauce sometime around 1998.

I was there because conferences make you do strange things.

You go where the herd goes.

You drink what’s handed to you.

You pretend you’re not exhausted even though your badge is still around your neck like a warning label.

I was holding a bourbon that tasted, somehow, like both a reward and a consequence.

And that’s when I saw Peter.

British. Calm. Standing at the bar like someone who’d been accidentally teleported into the wrong movie but was determined to make the best of it. He looked like the only man in the room who didn’t have anywhere else he needed to be, which immediately made me suspicious, because I never feel like that.

We’d met earlier that day through a mutual acquaintance, the sort of handshake you expect to forget by dinner. He worked in the nonprofit world—CEO of something with a name long enough to sound important. I had my scrappy little agency, my scrappier sense of direction, and a business model I was still making up as I went. He had presence. I had a badge with my name misspelled.

But somehow, standing there at the bar, we found ourselves talking.

Not networking.

Not trading résumés disguised as conversation.

Just… talking.

About work. About family. About that gnawing ambition that never quite matches the energy you actually have. And somewhere in the middle of the din, in a bar full of people line-dancing without irony, I felt myself unclench a little.

Peter had that effect.

He made you forget to perform.

At some point—maybe after the second bourbon, maybe after he deadpanned something so British it should have come with subtitles—I said something self-deprecating about being stretched too thin. About trying to keep every plate spinning even though some of them were clearly already broken.

Peter nodded like I’d said something worth hearing, then set down his glass and said, almost offhand:

“You know, there aren’t that many things that really matter.

Love your family.

Love your friends.

And do what’s in front of you.”

No sermon.

No warning that something meaningful was about to be said.

Just Peter, stating a fact about the universe as casually as if he were noting the humidity.

I laughed.

Not because it was funny, but because I didn’t know what else to do with something that simple.

But simplicity has a way of sneaking up on you.

The night blurred around that sentence—the too-loud band, strangers shouting over the music, the sticky floor, the bourbon pretending it was smoother than it was. And somewhere in that mess of sound and neon, something settled. Not dramatically. Just… like a coin finding the bottom of a fountain.

We kept talking, and laughing, and telling stories. There was a moment when he dryly mimicked an American trying to pronounce “Worcestershire,” and I realized I’d probably follow this man into any strange bar in America just to hear what he’d say next.

We didn’t know it then, but that was the beginning of a friendship that would anchor years of my life. The kind that builds itself slowly, without announcements. Dinners. Drinks. Conversations that wandered all over the map. His humor was surgical; his presence, disarming. He looked at you the way very few people look at anyone—with full attention, like the moment wasn’t a rehearsal for anything else.

And without ever meaning to, he handed me a way of being in the world.

Not a philosophy.

Not advice.

Just the Peter-ness of Peter.

His quiet steadiness.

His attention.

His way of showing up to the exact moment he was in.

As if that moment was enough.

As if that was the point.

He never explained what he meant.

He never needed to.

I think about that night more often than I expect to—not the noise or the bourbon, but the feeling of standing next to someone who seemed entirely unbothered by the present moment. Sometimes, when I’m stretched thin or trying to live three days ahead of my own life, I can almost hear him beside me:

“Just do what’s in front of you.”

Not guidance.

Not correction.

Just a reminder from a friend who lived that way without trying to convince anyone else to.

I didn’t know, back in that Nashville bar, that I’d spend years carrying his voice around with me. Or that one day I’d be carrying it without him. Grief is strange like that. It doesn’t shout; it taps you on the shoulder in the middle of an ordinary moment and asks if you remember.

And I think that’s why it stuck.

Because some people teach you things by accident.

Just by being exactly who they are, exactly when you needed them.

Even if you didn’t know it then.