“No man needs a vacation so much as the man who has just had one.”

Elbert Hubbard

Every family has a story that refuses to die.

For us, it’s Waltonia.

We were a road-trip family—not the carefree, singing-in-the-car kind, but the “let’s see how long we can tolerate each other in a confined space” kind.

My parents and I would pack the car like we were fleeing a war, then immediately realize we’d forgotten something important—like patience. They’d debate where we’d live after “the lottery win,” a recurring fantasy treated less like a daydream and more like an annual performance review. My mom always dreamed of Tuscany or France. My dad preferred anywhere with a Whataburger nearby.

We’d taken plenty of trips like that, but none that would become legend. Waltonia wasn’t even our idea—it came recommended by one of my dad’s co-workers, a man whose travel advice we’d later rank somewhere between questionable and litigious.

He couldn’t say enough good things about it. Called it a “hidden gem,” which, in hindsight, should’ve been a red flag. Things don’t usually stay hidden because they’re incredible.

Still, my dad trusted him. They worked together, which apparently carried the same weight as a blood oath. So we booked it and hit the road.

The brochure promised “rustic comfort along the Guadalupe River,” which sounded charming and vaguely European. We pictured something out of a magazine spread—rocking chairs on wide porches, gentle breezes through cypress trees, my parents laughing over iced tea while I skipped stones in slow motion.

In reality, Waltonia was… different.

Less rustic comfort and more mosquito cooperative with branding. The cabins came “with or without windows,” which felt less like an amenity and more like an oddly specific warning. The river moved slow and green, thick with water snakes that seemed far too confident about their place in the ecosystem. The humidity could’ve been bottled and sold as soup.

Out front, a sun-faded sign announced Welcome to Waltonia Lodges!—the exclamation mark doing most of the heavy lifting.

We pulled in late afternoon, the sun sitting heavy and low—like even it didn’t want to be there. The gravel popped under the tires as my dad tried to sound upbeat.

“This looks nice,” Dad said, the way someone might comment on a body at an open-casket funeral.

My mom squinted through the windshield. “Which one is ours?”

Dad pointed to a cabin that leaned slightly to the left, as if it were trying to get away from itself.

When we stepped out, the air wrapped around us like a damp towel.

Somewhere in the distance, a cicada screamed its resignation to God. The smell was equal parts river water, mildew, and whatever lives inside window-unit air conditioners.

Inside, the cabin had… character. The kind of character that comes from decades of guests and zero renovations. Technically, it had windows—though that felt like a generous interpretation. They didn’t open, but the curtains fluttered just enough to suggest hope. The air was still and heavy, the kind of heat that made furniture feel sentient. A single ceiling fan creaked above us, bravely doing nothing.

My mom took a slow look around and said, “It’s very… rustic.”

In that moment, rustic was code for non-refundable.

My dad, ever the optimist—or at least the man who had put down the deposit—clapped his hands once and said, “Well, this’ll do just fine.”

It was less a declaration and more a peace treaty with reality.

He unpacked like a man determined to enjoy himself: cooler first, then a stack of folding chairs, then the kind of forced cheer that smells faintly of denial. Within minutes he had claimed a spot on the porch, facing the trees as if it were a scenic overlook instead of a gravel parking lot.

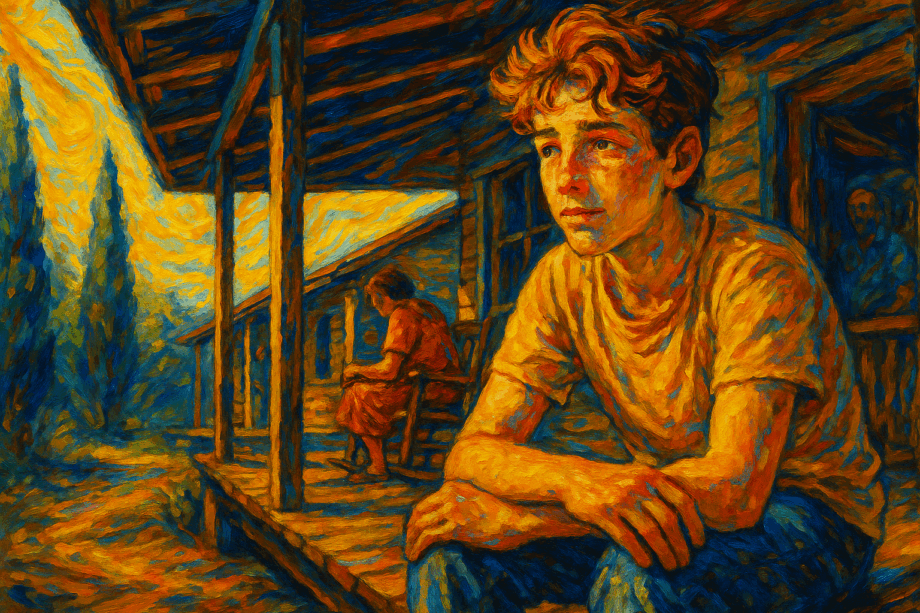

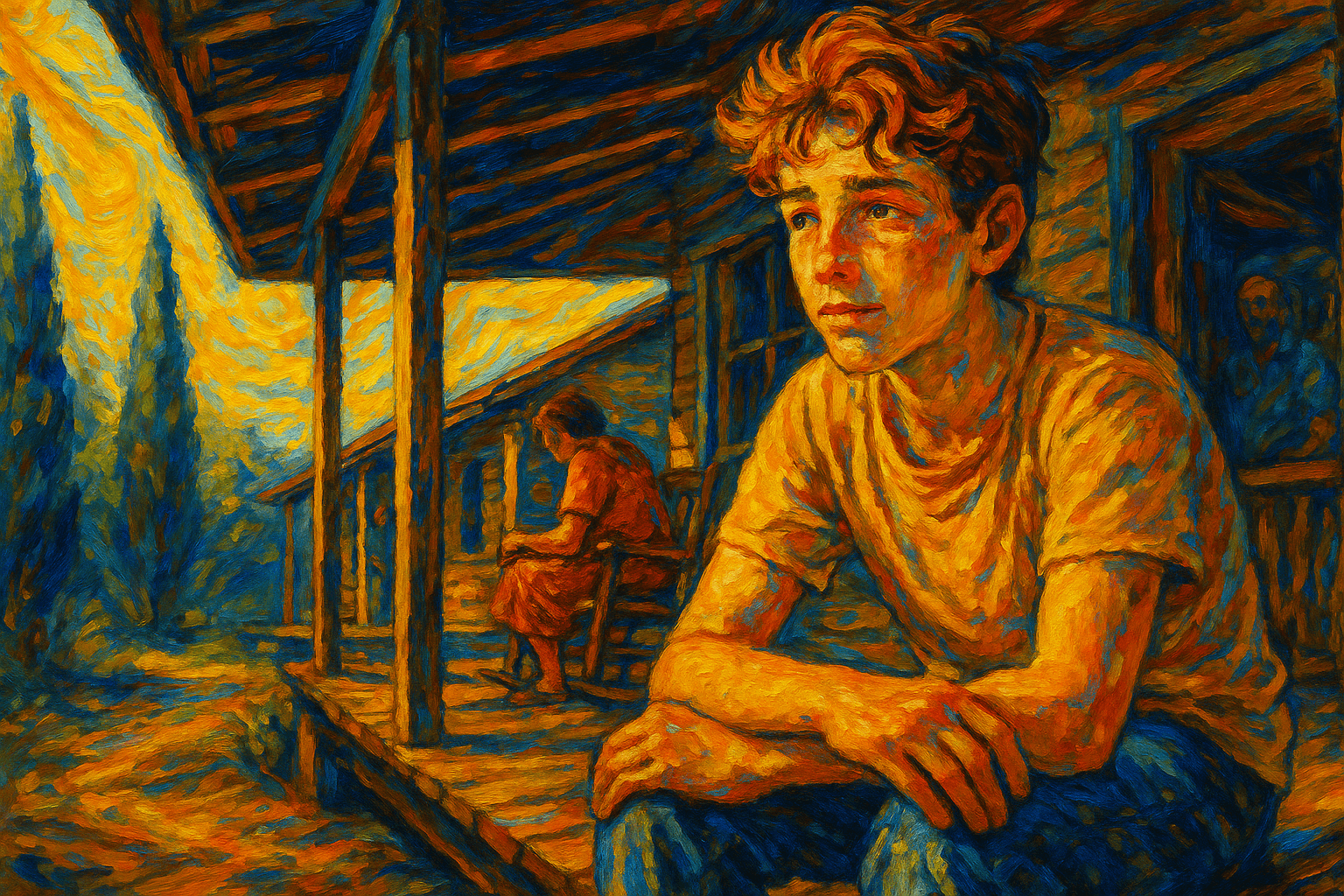

I followed him out, mostly to see what “fine” looked like in practice.

The air was syrupy; every step felt like walking through someone else’s breath. Still, there was something oddly peaceful about it—the hum of cicadas, the slow sway of trees, the smell of sunburn already setting in.

From the porch, I could hear my mom inside, still trying to sound optimistic. Cabinet doors opened and closed. A few words floated out the screen door—first in English, then in Spanish, then somewhere in between. Each one came a little sharper. By the third, we knew things had taken a turn.

“Another spider!” she shouted, her voice somewhere between disbelief and surrender. “¡Hay arañas por todas partes!”

That’s when I knew the battle for Waltonia had begun.

By sundown, the porch light had attracted every flying insect in the county. My dad sat in his folding chair, drinking what I remember as either a Diet Coke or a Miller Lite—something cold, at least—and insisting the bugs “weren’t that bad.” It was an argument he was clearly losing.

Inside, my mom was wilting.

There was no air conditioner, just a fan that sounded like it was pleading for mercy. The air didn’t move so much as hover. Sweat rolled down her temples, and she fanned herself with the Waltonia brochure, which by then felt like false advertising. Every few minutes came a sharp ¡Mier…coles! followed by the slap of a sandal and the rustle of paper towels.

At one point my dad poked his head in to check on her.

“Oh, that’s just a daddy long legs,” he said, as if identifying the species made the experience educational.

My mom didn’t find that comforting. “No importa cómo se llama!” she shouted back. I don’t care what it’s called!

Dinner was sandwiches, chips, and resignation. The stove might have worked, but no one was willing to find out. We ate with the door open, hoping for a breeze that never came.

Afterward, my dad declared that Waltonia “really grew on you.” My mom said she was fine, which translated, roughly, to “we’ll talk about this later.”

The cicadas hummed louder. The porch light flickered. Somewhere out in the dark, the river kept moving—slow, green, and full of secrets I hadn’t yet found a reason to discover.

That night we all tried to sleep in the same room—the only room—us and the daddy long legs. The fan ticked overhead, bravely pretending to circulate air that had no interest in moving. Every surface was warm: the beds, the walls, the air itself. Even the shadows looked sweaty.

My dad stretched out on one bed, hands behind his head, declaring, “This isn’t so bad,” which was how you knew it was. Five minutes later he sat up and said, “You feel that breeze?” There was no breeze. “Huh,” he said, lying back down. His voice had that quiet edge of a man negotiating directly with his choices.

My mom lay beside him, eyes open, whispering small prayers in Spanish that I’m fairly certain weren’t for our safety but for an early checkout. She fanned herself slowly, like a woman trying not to create any additional heat.

I stared up at the ceiling, watching a spider navigate one corner like it had paid for the place too. Somewhere in the dark, my dad sighed. Then the fan sighed. Then the rest of us joined in.

If paradise and purgatory shared a border, this might’ve been the checkpoint in between.

By morning, the fan was still ticking—slower now, like even it was reconsidering its life choices. None of us had really slept. My dad got up first, moving quietly so as not to wake the heat. He stepped outside with his coffee—or maybe a Miller Lite, hard to say—and sat on the porch, staring into the middle distance like a man doing the math on every decision that led him here.

My mom was already packing imaginary bags in her head. “Maybe we just stay one more night,” my dad offered through the screen door, voice hopeful but fading fast. She didn’t answer.

I decided to escape before things got worse.

The air outside was already thick, but at least it was moving. The path to the river wound through dry grass and the kind of trees that always look a little disappointed. The sound of cicadas was louder now, almost electric.

And that’s when I saw her.

She was sitting on the swing set near the pecan tree—barefoot, reading a book, and looking exactly like someone who belonged somewhere better than Waltonia. The sunlight caught her hair, or maybe that’s just how I remember it. She looked up, smiled, and said something like, “Hey.”

It was the first cool moment of the entire trip.

By midafternoon, the heat had gone from unpleasant to biblical. My mom was done pretending to enjoy it, and my dad—whose optimism had run out of shade—suggested we “go into town.”

That’s how Waltonia families said surrender.

There was an Oktoberfest happening nearby—polka music, sausages, the promise of air-conditioning. They told me I could come along, but it was the kind of invitation that comes with an escape clause. “You can stay if you want,” my dad said, glancing at me with a half-smile that could have meant go get the girl or we’d like a moment alone with beer and German brass bands.

So I stayed.

The girl from the swing set was there again, barefoot and reading, the book resting against her knees. I walked over and said something—what, exactly, I couldn’t tell you. But she laughed, and I laughed, and somehow that was enough to count as conversation.

We spent the afternoon talking, or something close to it. She told me about her school back home, her friends, her dog. I told her about the water snakes, as if I were their appointed ambassador. Time slid by in that strange, elastic way it does when you’re thirteen and someone is actually listening.

When her parents called her for dinner, she stood up, brushed the dust from her dress, and said, “See you later.”

It wasn’t a promise, just a phrase—but it felt like one anyway.

We left Waltonia the next morning with the windows down, hoping to coax in some cooler air. Even the car seemed grateful to be leaving.

My mom didn’t say much. She just stared straight ahead, her sunglasses hiding the expression that said never again. My dad tried to lighten the mood by listing everything we’d “learned” on the trip, starting with, “Always read the fine print about windows.” He got a small laugh for that, which I think he took as forgiveness.

I sat in the backseat, quiet but different.

I kept thinking about the girl from the swing set—how easy everything had felt for a few hours. How she’d listened like I actually had something to say. It wasn’t love, or anything close to it. It was just proof that I could step into a moment instead of watching it pass.

By the time we hit the highway, Waltonia was already taking its place in family lore. In the years that followed, whenever a trip went sideways—when a hotel overbooked or a rental house promised “charm”—someone would shake their head and say, “Well, at least it’s not Waltonia.”

And that’s the funny thing: we took better vacations, longer ones, even fancier ones—but this is the one that stuck. The one that turned into a story.

Every family has one that refuses to die.

For us, it’s Waltonia.